In the beginning, even before computer screens existed, serial interfaces were used to connect keyboards and teletypes to central processing units. Information typed on the keyboard could then be printed on the "teletypes" which later became known as printers. The first computer screens which also used serial interfaces, were commonly called "Glass Teletypes" because they emulated the teletype printers without using paper.

Since then, serial interfaces have been used to connect almost every imaginable type of device including:-

- keyboards

- printers

- screens

- modems

- computers

- computer terminals

- barcode scanners

- customer displays

- cash drawers

Some devices only ever receive data, such as a computer screen, printer or customer display.

Other devices both send and receive data, such as modems, computers and terminals.

The fact that serial interfaces can work reliably to connect all of these types of devices indicates how flexible this type of interface really is.

This flexibility however, has resulted in some of the most serious drawbacks to the serial interface. This is because it has led to a great range of interpretations as to how the RS232 standard should be applied, resulting in differences between manufacturers. While many of these differences no longer a problem because certain conventions have been adopted that is not always the case.

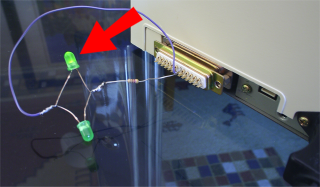

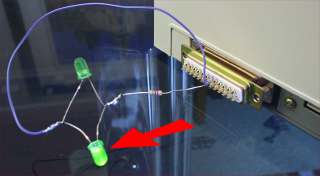

The serial interface is clearly bi-directional, or in other words, capable of passing data in both directions. But not every device actually sends data both ways. Often the manufacturer of Customer Pole displays figure that this device will never send data, so why build in the parts of the interface that send data? But the manufacturer of the computer that you are trying to connect to this customer display has implemented communication both ways and the interface on the computer end won't work until it receives signals from the device on other end that everything is OK... Signals that the other device never provides because it knows it will never use them.

To make things worse, the technical documentation supplied by the equipment manufacturers is, often as not, just plain wrong and misleading.

All this might sound very bad. The good news is that if you understand how serial interfacing actually works then you can make any serial device connect to any other serial device without a great deal of difficulty. And without having any of the technical documentation from the manufacturer. To illustrate how to interface serial devices without any documentation, we are going to interface this old receipt printer so that it works with SELLmatix Point of Sale running on a PC.

First, a few more details about serial interfaces and how they work.